Fungal biosonification: Making music with mushrooms

- A bit of history: bio-signaling in the 20th century

- The heart of the movement: key artists and projects

- Pioneers and viral figures

- Physical integration: when mushrooms play instruments

- Installations and conceptual explorations

- Gadgets and technique: technology as translator

- Capture devices and the sonification process

- Accessibility and the ‘Maker’ culture

- Possibilities and reach: beyond curiosity

- Environmental and educational implications

- Scientific studies and applications

- Debate and skepticism: art or noise?

- Scientific critique

- Artistic and philosophical authenticity

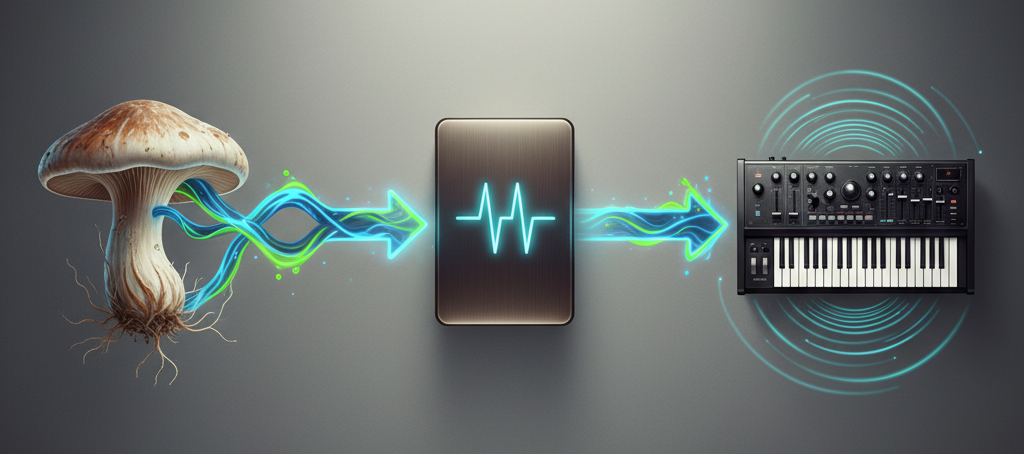

Mushrooms have neither vocal cords nor lungs, yet somehow they can make music. Or rather, we can listen to their electricity transformed into sound. That’s the essence of fungal biosonification: turning the natural electrical fluctuations of fungi into musical notes using MIDI technology.

In this process, bioelectrical impulses—tiny variations in the conductivity of their tissues or mycelium—are translated into digital data that control synthesizers. The result is not a “mushroom song” but a sound interpretation of its biological activity. A bridge between the organic and the electronic.

In recent years, this phenomenon has conquered social media. On TikTok and Instagram, millions of people have discovered musicians such as Tarun Nayar, creator of the project Modern Biology, connecting electrodes to an oyster mushroom and letting a modular synthesizer respond to its electrical rhythm. What began as a scientific curiosity has become a global artistic movement: a new way to unite ecology, science, and electronic music.

A bit of history: bio-signaling in the 20th century

Although mushrooms are the current stars, the concept of listening to biosignals isn’t new. Its origins trace back to the 1960s and 70s with figures like Cleve Backster, who claimed that plants reacted to thoughts and emotions (“plant perception”). While much of that early research lacked modern scientific rigor, it laid the foundations for exploring bioelectricity as a data source. From this early curiosity, technology and art have refined the process, seeking collaboration rather than mystical interpretation.

The heart of the movement: key artists and projects

Pioneers and viral figures

The most visible name of this current is Tarun Nayar, a Canadian biologist and musician. His project Modern Biology blends ambient art, electronic improvisation, and experimental biology. Nayar uses the bioelectrical energy of mushrooms and plants to control the tone and rhythm of his synthesizers, creating pieces that seem to breathe with the mycelium.

Another prominent figure is Noah Kalos, better known as MycoLyco. His approach leans away from ambient music and toward psychedelic trance: rhythmic beats and hypnotic atmospheres generated live with the electrical signals of living fungi. His performances blend biotechnological experimentation and musical performance, turning each set into a literal collaboration between human and fungus. Artists such as Jo Blankenburg, in turn, explore the integration of these biological data with Artificial Intelligence systems, creating generative music from fungal life.

Physical integration: when mushrooms play instruments

In the United Kingdom, the collective Bionic and The Wires has taken the idea even further. Their system translates MIDI data from fungi into motor signals that control robotic arms. These arms then play physical instruments—keyboards, drums, guitars—allowing mushrooms to “perform” musical pieces in real time.

What once seemed like an eccentric experiment has turned into a performance experience: the fungus as the invisible conductor of a robotic orchestra.

Installations and conceptual explorations

Artist Eryk Salvaggio, with his project Worlding, approaches biosonification from a more philosophical perspective. In one installation, he used an oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) connected to electrodes while illuminated by a lamp. Minutes later, the readings showed voltage spikes, as if the fungus were “reacting” to the light. It wasn’t a conscious response, of course, but a detectable biological signal—a kind of interspecies dialogue translated into sound.

Long before viral trends popularized this practice, British artist and composer Mileece had already spent over two decades working on the sonic transcription of plant electrical signals. Her pioneering vision established the basis for understanding biosonification not just as a technical experiment, but as a poetic language between species.

Gadgets and technique: technology as translator

Capture devices and the sonification process

Today, anyone with curiosity can experiment with biosonification thanks to devices like PlantWave or PlantsPlay 2, the most popular in this field. Both operate with electrodes or clips attached to the surface of the mushroom or mycelium.

These sensors detect changes in electrical conductivity, which are then sent to the device and converted into MIDI data. Some species, such as the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), are especially valued for their electrical “activity,” producing rhythmic patterns and variations more pronounced than those found in plants.

In essence, the technical flow follows three steps:

- Biosignal: The fungus produces a variation in electrical conductivity.

- MIDI device: The hardware (commercial or homemade) receives the signal and translates it into MIDI data.

- Synthesizer: The sound module reads the MIDI and converts it into audio.

The fungus produces the signal, but the artist chooses the instrument, scale, and effects. It’s a creative dialogue: biology provides randomness, the human provides design. From this collaboration emerge soundscapes that range from meditative to eerie—always unique and unrepeatable.

Accessibility and the ‘Maker’ culture

Beyond commercial equipment like PlantWave or PlantsPlay 2, biosonification has flourished within the maker (DIY) culture. This movement relies on low-cost microcontrollers, mainly Arduino, to replicate and expand the functionality of biodata devices.

Arduino, the heart of the DIY kit

The key to this democratization lies in the fact that a fungus’s bioelectrical signal, once properly amplified, is essentially a change in conductivity that can be read by the analog port of any Arduino board. Programmers, biologists, and self-taught musicians have used this to create:

- Open-source schematics and tutorials: On platforms like Reddit and GitHub, dedicated repositories (such as Biodata Sonification Kits) provide code and component lists for building amplification circuits, often at a fraction of a commercial unit’s cost.

- Citizen science: This has turned biosonification into an exercise in citizen science, where anyone can study the bioelectrical response of their own fungal cultures and contribute to collective knowledge.

Software and creative mapping

Once Arduino captures conductivity fluctuations, the next step is to send this data into a programming environment. Here, music-hacker culture comes into play, using open-source and visual programming tools such as PureData (Pd) or Max/MSP. These tools allow the artist to:

- Customize the mapping: Decide exactly which fungal parameter controls which sound element (e.g., a quick voltage spike might trigger a kick drum, while a slow change modulates tone or reverb).

- Free experimentation: Liberate art from factory presets, pushing sonic experimentation beyond app defaults.

This technical accessibility has been key to turning fungal music from a niche curiosity into a global DIY art movement.

Possibilities and reach: beyond curiosity

Environmental and educational implications

For many artists, the value of this practice goes far beyond sonic novelty. Fungal biosonification has become a way to reconnect with nature, to remember that mycelium is alive, active, and part of a biological language we are only beginning to grasp.

In workshops and exhibitions, mushroom music is used as a teaching tool to explain fungi’s crucial ecological roles, nutrient recycling functions, and invisible underground communication networks. Listening to a mushroom “play” becomes an auditory metaphor for that hidden life.

Scientific studies and applications

In the scientific realm, some researchers are exploring how sound and vibration influence fungal growth. Experiments with species like Trichoderma harzianum suggest that certain frequencies may stimulate spore or enzyme production.

Meanwhile, biosonification offers a potential method for studying bioelectrical communication within mycelial networks, enabling researchers to map how colonies respond to external stimuli such as light, humidity, or contact.

Debate and skepticism: art or noise?

Scientific critique

Not everyone is convinced. Many scientists argue that mushroom bioelectrical fluctuations are too slow or weak to yield complex melodies. What we hear, they say, might simply be amplified electrical noise or environmental interference.

Even so, artists maintain that the value of the process lies not in its scientific purity but in the creative mapping of this data into musical scales. What science calls “noise,” art transforms into rhythm, texture, and emotion.

Artistic and philosophical authenticity

There’s also a more philosophical question: is the fungus the composer, or merely a biological controller within a human instrument? Where does authorship begin and end?

This question resonates with theories of deep ecology and sonic posthumanism. Inspired by thinkers such as Donna Haraway, the value of this music lies in decentering human authorship, recognizing the fungus as an organic co-creator. It’s an act of radical listening that challenges musical and biological hierarchies, suggesting that intelligence isn’t a human monopoly.

More than a viral trend, fungal biosonification is an act of listening. In an age saturated with digital noise, turning a mushroom’s electricity into music brings us back to something primal: the awareness that life has rhythm, that biology pulses, and that beneath the roots of the forest, a melody is hidden.