Fusarium venenatum, the fungus challenging the meat industry's efficiency

The global protein industry is going through a phase of silent exhaustion. Over the last decade, the dominant response to the environmental and ethical crisis of livestock farming has been the proliferation of plant-based products that mimic meat: pea burgers, soy sausages, starch matrices, and lab-reconstructed aromas. They have managed to reduce emissions and open the debate, but they haven't convinced everyone. Not the palate, not agricultural systems, nor energy balance sheets.

In this context, science has begun to look more closely at a territory that is neither animal nor vegetable: the fungi kingdom. Not as a culinary trend, but as a mature biotechnological platform, capable of producing high-quality protein with a metabolic efficiency that traditional agriculture cannot match.

The turning point came in November 2025. A team of researchers from Jiangnan University (China), led by Dr. Xiao Liu, published an advance in Trends in Biotechnology that changes the rules of the game. Using precision gene editing, they managed to optimize the fungus Fusarium venenatum to convert it into a significantly more productive and cheaper source of protein. This was not a futuristic promise, but a concrete molecular unlocking with immediate results.

Redesigning fungal metabolism

Mycoprotein is not a recent discovery nor an improvised response to climate anxiety. Fusarium venenatum is an old acquaintance, identified as a food candidate back in the 1970s, in a context marked by energy crises and fear of shortages. When it hit the market in the 1980s (under brands like Quorn), its proposal was radical for the time: producing protein in fermentation tanks, without fields, without pastures, and without animals.

However, that first generation arrived with limitations. Its industrial production has always clashed with a biological limit: the speed at which the fungus can assimilate nutrients, specifically nitrogen. For decades, Fusarium survived as a niche solution, with high costs and an efficiency that didn't quite take off.

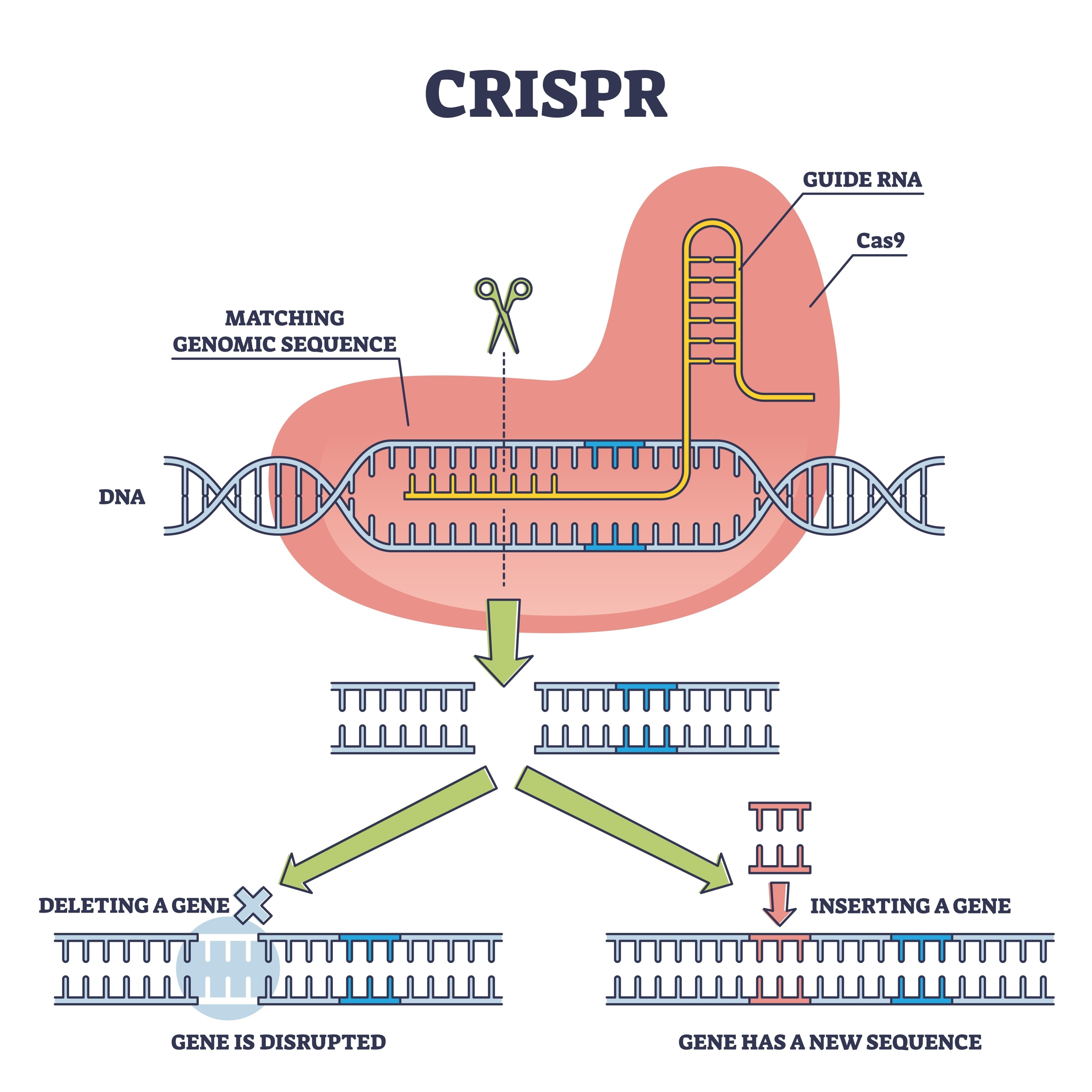

This is where Xiao Liu's team comes in, rescuing this technology to place it in a position to compete. They opted for a strategy of "cisgenesis." Unlike classic transgenics, where DNA from other species is introduced, here the CRISPR-Cas9 tool was used to edit genes that already existed in the fungus. The target was a specific gene family: glnA, responsible for the production of glutamine synthetase. This enzyme acts as a metabolic "gatekeeper"; in the wild strain, it limits the amount of nitrogen the fungus absorbs to build proteins.

By modifying the promoters of these genes, the researchers managed to release the organism's "handbrake." The result is a fungus that optimizes its internal metabolism to stop regulating its growth downwards, converting nutrients into biomass with unprecedented voracity.

Biomass increase and cost reduction

In the food industry, sustainability is a mathematical equation. If the final product is expensive or slow to produce, it will not replace meat. The results presented by Jiangnan University attack precisely that equation with compelling figures:

- Growth explosion (+88%): Under identical culture conditions, the edited strain almost doubles its biomass compared to the natural variant. This allows fermentation plants to double their production without needing to build new bioreactors, drastically reducing the necessary capital investment.

- Resource savings (-44%): The modified fungus needed almost half the sugar to grow. Given that the culture medium (the fungus's "food") represents one of the largest operating costs, this efficiency is the key to achieving price parity with cheap industrial meat.

If we contextualize these data, the abyss with livestock farming widens. The production of this mycoprotein emits between 60 and 70% less greenhouse gases than beef and eliminates deforestation and massive water consumption from the equation. It is industrialized protein, yes, but without the ecological burden of the traditional meat model.

Even so, efficiency is not an automatic promise. In biotechnology, lab results do not always survive the leap to industrial scale. An organism that grows voraciously under controlled conditions can behave unpredictably in bioreactors of hundreds of thousands of liters, subjected to temperature variations, oxygenation issues, and prolonged metabolic stress.

The study authors themselves point out that the next challenge will be to evaluate the genetic stability of the edited strain over the long term, as well as its behavior in continuous production cycles. The history of food biotechnology is full of brilliant advances that failed not due to a lack of science, but due to practical limits. This Fusarium has gained speed; now it must demonstrate endurance.

But producing more protein is useless if the human body cannot utilize it. And that is where fungal biology posed, until now, one of its greatest limits.

More nutritious and digestible: how gene editing redesigns fungal fiber

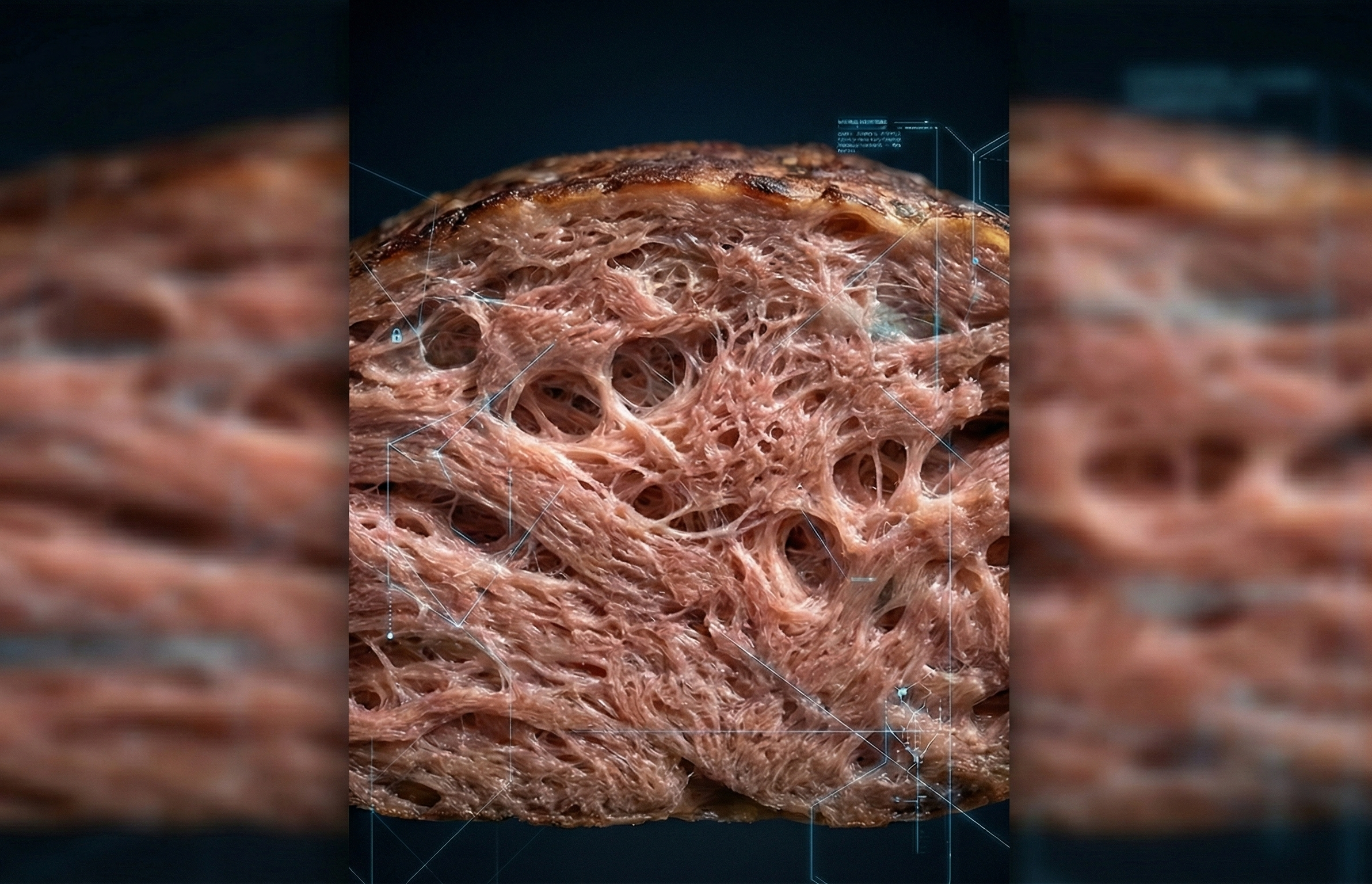

The consumer does not buy proteins; they buy an experience. Fiber, bite, juiciness. This is where fungal biology offers a structural advantage: it grows forming hyphae, microscopic filaments that naturally mimic the arrangement of animal muscle fibers.

However, that architecture had a hidden price: bioavailability. Fungal cells are protected by rigid walls of chitin—the same material as insect exoskeletons. Until now, for the human digestive system, breaking that "armor" proved complex, preventing access to much of the protein the fungus stores inside. We had a food rich in theory, but not always utilized with the efficiency its composition promised.

The Jiangnan team addressed this obstacle with a second round of gene editing, parallel to the growth one. They eliminated genes associated with chitin synthase, significantly reducing the thickness of the cell wall.

The result is a delicate biotechnological balance: the hyphae maintain their interwoven structure (preserving the meaty texture), but their defensive walls are now thinner. By "thinning" that barrier, researchers released the intracellular protein so our body can actually absorb it. It is no longer just a food that "fills" due to its fiber, but one that nourishes with the promised efficiency.

Although Liu's study focused on growth and digestibility, the field is advancing towards flavor. Other recent research uses similar techniques to induce the production of hemoproteins—responsible for the metallic taste of meat—promising to close the definitive sensory gap between the fermenter and the slaughterhouse.

Industrial scaling and regulatory framework

It is no coincidence that this advance comes from China. In the last decade, the country has identified precision fermentation as a strategic technology, capable of reducing its dependence on agricultural imports and buffering the volatility of global protein markets.

Fungal protein does not just compete with meat: it competes with the extensive agricultural model, with global logistics, and with the geopolitics of food. On that board, bioreactors become infrastructures as critical as grain silos or commercial ports.

The scientific advance is undeniable, but the path to the supermarket passes through bureaucracy. However, the technique chosen by Xiao Liu's team could facilitate the process. By not incorporating exogenous DNA, these fungi fall into a favorable regulatory zone in regions like the United States and, increasingly, the European Union, where a distinction is starting to be made between classic Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) and Edited Organisms (NGT). The logic is that, by not introducing genetic material from foreign species, the final result is considered biologically equivalent to a mutation that could have occurred in nature. This allows bypassing the strict and costly safety protocols required for classic transgenics.

In a fermentation plant, there are no meadows or pens. Only steel tanks, pipes, and a constant murmur of moving liquids. The fungus grows without seeing sunlight, transforming sugars and nitrogen into edible fibers with an efficiency no animal can replicate. There is no slaughter nor rural epic: only optimized metabolism.

Perhaps that is the reason why this revolution advances in silence. It does not appeal to nostalgia or emotion, but to an uncomfortable question: what are we willing to leave behind to keep feeding ourselves without depleting the planet.

In a world approaching ten billion inhabitants, the question may not be if we will accept eating fungi, but what other ideas about food we will have to abandon to keep feeding ourselves without depleting the planet. Liu's proposal offers a sober solution: abundant, efficient, and cheap protein, cultivated in the dark to let the planet recover the light.

Sources and references

- Liu, X., et al. (2025). Dual enhancement of mycoprotein nutrition and sustainability via CRISPR-mediated metabolic engineering of Fusarium venenatum. Trends in Biotechnology.

- Finnigan, T., et al. (2019). Mycoprotein: The Future of Nutritious Nonmeat Protein, a Review. Current Developments in Nutrition.

- Regulation and Market:

- On regulatory approval in China (2025): China approves its first mycoprotein ingredient

- On food safety: How gene-edited crops are regulated around the world (Nature).

- Wiebe, M. G. (2002). Myco-protein from Fusarium venenatum: a well-established product for human consumption. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology.