The evolutionary enigma of psilocybin

- The phylogenetic mystery: the paradox of time

- Genetic exchange between species

- The molecular signature of the "loan"

- The ecological context of the exchange

- Multiple paths toward the same molecule

- The current scientific debate

- Psilocybin as chemical defense

- The ecological hypothesis

- Psilocybin: a molecule between ecology and medicine

- From the evolutionary "why" to the medical "what for"

- Sources and references

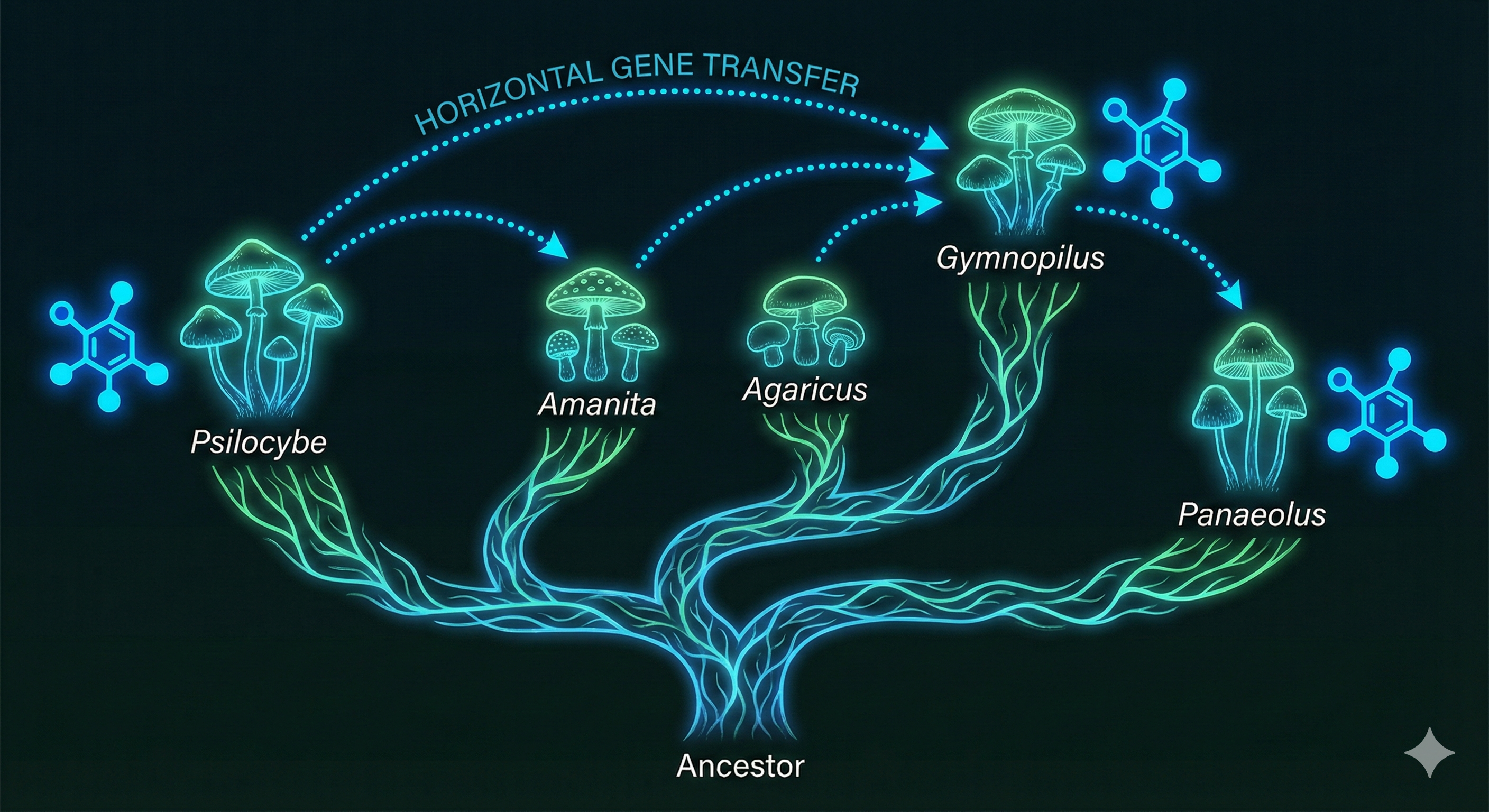

For decades, classical taxonomy reinforced a simple story: psilocybin was the exclusive property of the genus Psilocybe. Those known as magic mushrooms seemed the sole depositories of this molecule. However, this appearance-based view collapsed in the early 21st century: the arrival of comparative genomics revealed that this exclusivity was, in reality, an illusion.

Today we know that psilocybin appears in more than two hundred species spread across genera that are, phylogenetically, distant: Panaeolus, Gymnopilus, Pluteus, Inocybe. Some of these lineages diverged so long ago that they are as far apart on the tree of life as a human is from a lemur. Imagine finding exactly the same complex tool, manufactured with the same technique, in two civilizations that never had contact. In biology, that shouldn't happen without an exceptional mechanism behind it.

This ceases to be a curiosity and becomes an evolutionary anomaly. A clue that psilocybin is not a biological accident, but a solution so effective that nature has distributed (or reinvented) it recurrently through time.

The phylogenetic mystery: the paradox of time

To understand the dimension of the biological conflict, one must look at the geological clock. Recent research from the University of Utah (2024) places the origin of psilocybin in the genus Psilocybe about 67 million years ago. The date is no coincidence: it coincides almost exactly with the K-Pg extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs. In a darkened world full of dead vegetation, these fungi (originally wood-eaters) found their golden opportunity to diversify, before some lineages made the evolutionary leap toward dung.

If the ability to produce psilocybin came from a distant common ancestor (vertical inheritance), we would expect to see two things: a much wider distribution of the trait among thousands of descendant species, or at least, traces of degraded genes in those that lost the ability. This is what is known as pseudogenes or "genetic fossils." That is, if grandma left a cooking recipe to the whole family, we would expect to find the recipe intact in some grandchildren, and torn, incomplete, or crossed-out versions in others.

But they aren't there. The synthesis capacity appears discontinuously, in isolated genetic islands, while the vast majority of intermediate relatives completely lack that molecular machinery. The math of vertical inheritance doesn't add up: it is statistically unlikely to keep a complex trait silent during geological eras only for it to reappear intact in just a few chosen ones.

Genetic exchange between species

Here is where molecular biology introduces the hypothesis of Horizontal Gene Transfer (HGT). This mechanism breaks the golden rule of inheritance: instead of passing genes from parents to offspring (like a family library), organisms exchange genetic material between contemporary species, similar to copying a file onto a pen drive and installing it on someone else's computer.

The molecular signature of the "loan"

How do we know this happened? Because of topological incongruence, that is, when genetic trees do not match. When scientists sequence the genes responsible for psilocybin, they see that their "family history" does not match the history of the species that carry them.

A useful analogy: imagine you analyze the DNA of two European families with no known kinship and discover that both carry an identical gene typical of Asian populations. That gene "doesn't fit" in their European family tree, suggesting it arrived via another route (perhaps a traveling ancestor, an adoption, a historical event). Something similar happens in fungi: the psilocybin genes appear to be much closer relatives to each other than the fungi hosting them are, an unmistakable sign that they have recently jumped between lineages.

The ecological context of the exchange

This phenomenon is not magic, it is ecological. It occurs in shared niches of high microbial density, such as decaying logs or dung. In this biological "broth," where the hyphae of different species touch and compete, environmental stress can facilitate the absorption of exogenous DNA.

Furthermore, the psilocybin genes are not scattered but organized in a compact biosynthetic cluster. Being packaged together, it is possible to transfer the "complete recipe" in a single recombination event, saving the recipient millions of years of gradual evolution.

Multiple paths toward the same molecule

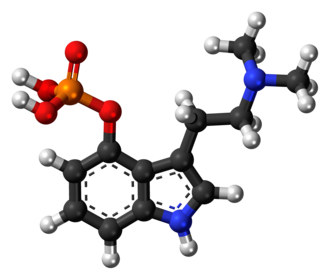

At a biochemical level, the system's efficiency is remarkable. Nature uses a standardized assembly line: four key enzymes (encoded by the genes PsiD, PsiK, PsiM, and PsiH) transform the amino acid tryptophan into psilocybin. It is a biological industrial process.

However, this assembly line is not as rigid as we thought. Recent genomic analyses (2025) have discovered that, even within the genus Psilocybe, there are two distinct arrangements for this gene cluster. This suggests that nature did not limit itself to copying and pasting the recipe just once, but rather the genetic machinery has been reorganized or reacquired on multiple occasions throughout the history of the genus.

The current scientific debate

In parallel, current science is debating fascinating nuances. While in genera like Panaeolus the evidence clearly points to HGT (direct copy), in other lineages like Inocybe variations appear in the enzymes or synthesis order. This suggests a mixed and more complex scenario: a combination of direct genetic exchange in some cases and pure convergent evolution in others.

That is, different fungi, subjected to similar pressures, have not only passed the tool around but on occasions have managed to design analogous tools via different paths. The molecular destination is the same, but the evolutionary route varies.

Psilocybin as chemical defense

There is an anthropocentric temptation that is hard to avoid: thinking that psilocybin exists to interact with the human mind. But evolutionarily, we arrived too late. Manufacturing such a complex secondary molecule implies a high metabolic cost; natural selection would penalize this expense if it did not offer an immediate vital advantage.

The ecological hypothesis

The strongest hypothesis is ecological: psilocybin acts as a chemical defense mechanism, designed to alter anyone attempting to eat the fungus. The main targets are not us, but mycophagous insects, competing termites, and gastropods (slugs and snails). In fact, it is theorized that the rapid oxidation of psilocin (the famous blue color upon touch) could act as a warning signal or specific unpleasant taste for these predators.

Recent experimental studies have shown that psilocybin alters neuronal signaling in invertebrates, suppressing appetite. Unlike humans, who experience perceptual effects through interaction with 5-HT2A receptors, in insects the effect is induced anorexia or motor uncoordination. An insect that loses interest in eating is an insect that does not destroy the fruiting body before it disperses its spores.

From the fungus's perspective, psilocybin is a selective neurotoxin designed to ensure reproduction. That we humans experience such distinct effects—and so subjectively significant ones—is a side effect of sharing serotonergic receptors with other animals, not the original purpose of the molecule.

Psilocybin: what it is, how it works and what effects it has

Explore what psilocybin is, how it is transformed into psilocin, and what experiences it can cause in the mind, body, and perception according to current neuroscience.

Read morePsilocybin: a molecule between ecology and medicine

From this perspective, psilocybin ceases to be a cultural mystery and becomes a case study in biological efficiency. It is a survival tool that proved so valuable that nature developed multiple pathways—from gene swapping to evolutionary convergence—to ensure its presence.

From the evolutionary "why" to the medical "what for"

Understanding that this molecule was designed by evolution to manipulate basic nervous systems offers us a rational basis for understanding its potency in the human brain. Psilocybin is not a "magic" substance in the esoteric sense, but it is in the biological one: it represents one of those molecular solutions so effective that evolution has reinvented it multiple times independently.

This knowledge is not just biological trivia; it has direct medical implications. Evolution designed a "master key" for a very ancient type of lock: serotonergic receptors. It turns out that insects and humans share versions of that same lock in our nervous systems. This helps explain why clinical trials show promising results in treating treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety associated with terminal illnesses. It is not coincidence: it is applied evolutionary chemistry.

Far from closing the debate, deciphering the evolutionary why of psilocybin is the necessary first step to rigorously investigate what we can use it for in future medical science. The molecule that a fungus developed to deter insects might end up being one of 21st-century psychiatry's most valuable tools.

Sources and references

- Reynolds, H. T., et al. (2018). "Horizontal gene cluster transfer increased hallucinogenic mushroom diversity". Evolution Letters. (Genetic evidence of HGT).

- Awan, A. R., et al. (2018). "Convergent evolution of psilocybin biosynthesis in fungi". BioRxiv / Fungal Genetics and Biology.

- Bradshaw, A. J., et al. (2024/2025). "Phylogenomics of the psychoactive mushroom genus Psilocybe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

- Malerba, S., & White, K. (2023). Studies on the ecological interaction between psilocybin and mycophagous insects and the chemical defense hypothesis.