Myths about psilocybin that science has debunked

- 1. Does psilocybin destroy neurons?

- 2. Does psilocybin generate physical addiction?

- 3. Is it as dangerous as other drugs?

- 4. Is it safe because it's natural?

- 5. Do hallucinations lack therapeutic value?

- The Default Mode Network (DMN)

- 6. Does psilocybin get stored in the spinal column?

- 7. Does it cure depression instantly?

- 8. Does psilocybin increase the risk of psychosis?

- Sources and references

For decades, psilocybin has lived two almost opposite reputations. In the 1950s it was studied as a promising clinical tool; shortly after, the "War on Drugs" turned it into a taboo that halted research for nearly forty years. Today, that silence has been broken: centers like Johns Hopkins, Yale, and Imperial College are recovering the lost work and providing solid data on its possible therapeutic utility.

But this return has also brought new oversimplifications. Psilocybin is no longer seen as a public enemy, but it shouldn't be celebrated as a miracle cure either. Its real role lies at an intermediate point, where potential benefits and risks that need to be understood coexist.

In this article we review the main myths that still surround psilocybin: what we really know, what's still under study, and what ideas should be left behind.

1. Does psilocybin destroy neurons?

A widespread belief in the 1980s, fueled by strong anti-drug campaigns, held that psychedelics caused irreversible brain damage, "frying" neurons or rendering them useless. Modern neuroimaging technology has completely debunked this myth.

Recent studies indicate that psilocybin not only does not cause neuronal death, but promotes the opposite:

-

Structural neuroplasticity: Increases the brain's capacity to change and adapt.

-

Synaptogenesis: Promotes the creation of new connections between neurons.

-

Global connectivity: Allows brain areas that are normally isolated to communicate with each other.

This state of malleability makes the experience depend largely on set & setting: the person's prior mental state (set) and the physical, emotional, and relational environment in which the substance is taken (setting). In a safe and accompanied context, neuroplasticity is oriented toward positive change; in a chaotic or threatening environment, it can amplify confusion or anxiety.

Therefore, we can say that the myth of "Psilocybin destroys neurons" is false.

2. Does psilocybin generate physical addiction?

For a substance to generate classic physical dependence (like heroin, alcohol, or nicotine), it usually needs two factors: to intensely activate the dopaminergic reward system and to cause severe physical symptoms when withdrawn. Psilocybin does not fit this pharmacological profile.

Its mechanism is different: it acts by agonizing serotonin receptors (mainly 5-HT2A). This results in three characteristics that distance it from addiction:

- Absence of "Craving": It doesn't activate the dopaminergic reward circuit like textbook addictive substances, causing that irrefutable physical desire for immediate consumption.

- Rapid tolerance: The body generates resistance almost immediately. Consuming psilocybin two days in a row makes the substance have almost no effect on the second day, which physiologically prevents continued compulsive use or "binging."

- No physical withdrawal syndrome: There are no medical records of physical collapse, tremors, or life-threatening risk after discontinuing its use.

For all these reasons, the belief that these hallucinogenic mushrooms are physically 'addictive' is debunked. Psilocybin does not hijack the brain's reward system, and the rapid tolerance it generates acts as a physiological safeguard against continued use. Far from creating a chain of need, the substance behaves in a self-limiting manner, making the myth of physical addiction unsustainable from a scientific standpoint.

3. Is it as dangerous as other drugs?

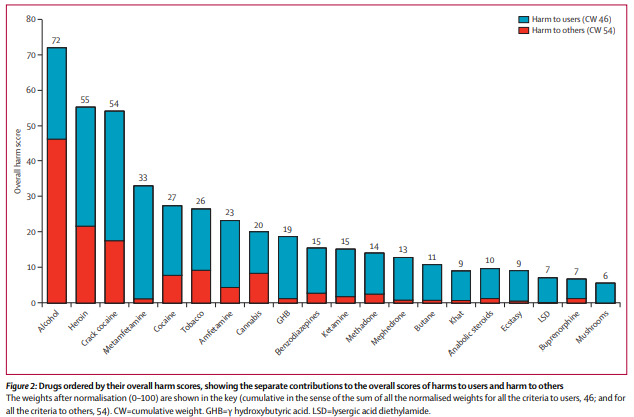

For decades, legislation has classified psilocybin in Schedule I (no medical value and high dangerousness), legally equating it with heroin. However, when science analyzes real toxicity and social impact, the picture is very different.

Professor David Nutt's study published in The Lancet (2010) evaluated the overall harm of 20 substances. The results drastically reordered the perception of danger: alcohol was positioned as the most harmful substance in global terms (maximum social harm), while heroin and crack led in direct harm to the user. At the opposite extreme, psilocybin mushrooms appeared at the end of the graph, with one of the lowest toxicity and social harm profiles recorded.

This leads us to an ironic conclusion: the law persecutes psilocybin with the severity reserved for deadly poisons, while science places it among the most benign substances for the organism. It's not as dangerous as other drugs in terms of public health or criminality. Its risk is not physical collapse, but emotional destabilization in unprepared users. Equating it with heroin is not only a scientific error, it's a legislative fallacy.

4. Is it safe because it's natural?

As a reaction to prohibitionism, the naturalistic fallacy emerged: the idea that because it's a fungus that grows in the earth, it's automatically benevolent. It's a dangerous reasoning. Nature produces deadly toxins (like that of Amanita phalloides or snake venom) as effectively as it produces medicines.

Psilocybin is a potent compound that alters cerebral hemodynamics. It can transiently elevate blood pressure and, more importantly, can trigger panic, confusion, or severe emotional dysregulation if the person is not prepared. The botanical origin of a molecule describes its provenance, not its safety profile.

Being natural is not synonymous with being harmless. The substance's origin doesn't exempt us from physiological or psychological risks. Therefore, the safety of psilocybin lies in knowledge, respect, and controlled environment (Set & Setting), and never in the simple fallacy that 'the earth does no harm.'

5. Do hallucinations lack therapeutic value?

Popular imagination tends to associate psilocybin with striking visual landscapes like moving colors, geometric patterns, or changing textures without value. However, in clinical research, these effects are secondary. What really matters is not what appears before the eyes, but what occurs at the emotional level and in the organization of brain networks.

The Default Mode Network (DMN)

This is where the Default Mode Network (DMN) comes into play, responsible for maintaining our sense of identity, internal narrative, and repetitive thought loops. In disorders like depression or anxiety, this network tends to function rigidly and overactively.

Psilocybin temporarily reduces DMN activity. This change facilitates two key processes:

- A subjective experience of disidentification: By decreasing the activity of the network that sustains the narrative of the self, some people feel a greater connection with their environment and a momentary distance from their habitual thought patterns.

- An increase in communication between brain networks: Regions that normally function in isolation coordinate more freely, which can help make deeply ingrained mental patterns more flexible.

Clinical studies suggest a relationship: the deeper this subjective experience (not necessarily visual, but emotional and cognitive), the greater the therapeutic improvement tends to be in the following days or weeks.

6. Does psilocybin get stored in the spinal column?

This is perhaps the most persistent urban myth without scientific basis. No study has found traces of psilocybin or psilocin accumulated in nervous system tissues. It's physiologically false. Psilocybin is rapidly metabolized in the liver into psilocin, and is eliminated from the body through urine within hours (generally less than 24h).

The body has no mechanism to "store" these molecules in the spinal cord or adipose tissue for years. The phenomenon of flashbacks, clinically known as HPPD (Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder), is a rare neurological condition related to visual processing, not drug deposits "hidden" in your back.

The human body doesn't function as a safe for hallucinogens. Once metabolized and excreted, the molecule disappears. Any persistent effect resides in how the brain processes information after the experience, never in phantom residues of the substance hidden in your vertebrae.

7. Does it cure depression instantly?

Some people experience rapid emotional relief after using psilocybin, not because the substance cures depression instantly, but because it temporarily modifies rigid thought patterns; sustained recovery depends on subsequent therapeutic work.

The substance opens a window of opportunity that lasts days or weeks after the session. But real change depends on integration. Without that subsequent psychological work to process what was experienced, interpret emotions, and apply behavioral changes in daily life, the experience can remain just an intense but ephemeral memory.

The substance facilitates the lesson, but it's the individual who must study, practice, and integrate that learning for the 'cure' to be real and lasting.

8. Does psilocybin increase the risk of psychosis?

Modern population studies refute the idea of a universal danger. Exhaustive research, such as that conducted analyzing data from national health surveys in the U.S. with over 130,000 participants, found no statistical association between lifetime use of psychedelics and an increase in rates of mental health problems or suicide in the general population.

In current controlled clinical trials, prolonged psychotic reactions (beyond the duration of the drug's effect) are extremely rare. For most people, the risk is extremely low; for those with clear psychiatric predisposition, it's a significant risk.

However, dismantling the stigma doesn't mean ignoring contraindications. In people with genetic predisposition to schizophrenia or diagnosed with bipolar disorder, psychedelics can act as a trigger, precipitating a psychotic episode that might not have manifested otherwise (or not so soon). For this reason, prior medical screening is the most important safety barrier in clinical trials and what radically differentiates therapeutic use from reckless recreational use.

Science is validating psilocybin's potential, but what we have today are promising indicators, not universal certainties. The neuroplasticity it induces can be a valuable therapeutic tool, but it depends entirely on context, preparation, and subsequent integration. In clinical settings and with professional accompaniment, it opens paths that conventional treatments don't always achieve. Outside that framework, it remains a potent substance that demands respect, caution, and a realistic understanding of its limits.

Disclaimer: This article is for strictly informational and educational purposes. Psilocybin is a controlled substance and its possession or use is illegal in most jurisdictions.

Sources and references

- Griffiths, R. R., et al. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology.

- Nutt, D. J., et al. (2010). Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis. The Lancet.

- Shao, L. X., et al. (2021). Psilocybin induces rapid and persistent growth of dendritic spines in frontal cortex in vivo. Neuron.

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., et al. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. PNAS.

- Johansen, P. Ø., & Krebs, T. S. (2015). Psychedelics not linked to mental health problems or suicidal behavior: A population study. Journal of Psychopharmacology.

- Passie, T., et al. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology.

- Various Authors (2021). Psychedelics and Neuroplasticity: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry.

- Dargan, P. I., et al. (2017). Harm potential of magic mushroom use: A review. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology.

- Krebs, T. S. & Johansen, P. Ø. (2013). Psychedelics and Mental Health: A Population Study. PLOS One.

- Additional research on metabolism and pharmacokinetics: