Complete guide to psychoactive mushrooms

Hallucinogenic mushrooms, also known as magic mushrooms, have been used for millennia in rituals, spiritual practices, and, more recently, in scientific studies on consciousness. Their visionary power comes from a variety of psychoactive compounds like psilocybin, which triggers profound psychedelic effects and alterations in perception.

With hundreds of species identified worldwide, these mushrooms are grouped into various genera and contain different active compounds. From the Psilocybe that grow in humid forests to the iconic Amanita muscaria, the world of hallucinogenic mushrooms is as diverse as it is mysterious.

In this article, we explore the most important psychoactive compounds, the main families of magic mushrooms, the most well-known species, and their psychedelic effects from a scientific and educational perspective.

What compounds make mushrooms hallucinogenic?

The psychedelic properties of these mushrooms come from various chemical compounds that primarily interact with the brain's serotonergic system. Here are the most significant ones:

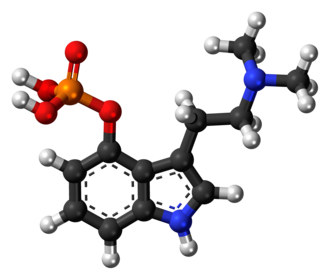

Psilocybin and psilocin

These are the most well-known and studied compounds. Psilocybin is converted into psilocin during metabolism, producing a wide range of effects, such as:

- Visual alterations (vivid colors, geometric patterns)

- Altered perception of time

- Deep introspective states

- A sense of unity or connection with nature

They are found in over 200 species, particularly in the Psilocybe genus. In regulated clinical settings, psilocybin is being researched as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression, existential anxiety, and addictions. Recent studies from institutions like Johns Hopkins and NYU have documented promising results in these areas.

Therapeutic applications of psilocybin

Psilocybin has gone from being a banned drug to a promising clinical tool. We explore how it is redefining the treatment of disorders such as depression, anxiety and addiction.

Read moreIbotenic acid and muscimol

Present in mushrooms like Amanita muscaria and Amanita pantherina, these compounds do not belong to the tryptamine family. Their effects include:

- Dreamlike or confusional states

- Motor disinhibition

- Archetypal or symbolic visions

Historically associated with shamanic rituals in Siberia and other northern territories, their consumption requires deep knowledge of preparation and dosage due to their potential toxicity. Toxicological studies have documented severe cases of poisoning, so recreational use is not recommended.

Other compounds: baeocystin and norbaeocystin

These psychoactive alkaloids are also found in various Psilocybes. Though less potent, they contribute to the overall effect of the mushroom in what is known as the "entourage effect". They are being studied as potential modulators of the psychedelic effect and their synergy with psilocybin.

What is the difference between a species and a strain?

Before diving into the types of hallucinogenic mushrooms, it’s important to understand the difference between species and strains. A species is a group of organisms that can reproduce with each other, such as all Psilocybe cubensis, which can interbreed to produce offspring. However, a Psilocybe cubensis cannot interbreed with a Psilocybe azurescens.

Strains, on the other hand, are subgroups within a species that vary in phenotypes or growth patterns, such as color, size, or potency. For example, within Psilocybe cubensis, there are over 100 strains, such as B+, Golden Teacher, or McKennaii, all with subtle differences but belonging to the same species. This can be compared to humans: a race (like Caucasian or Asian) is similar to a strain, with distinct characteristics but within the same species (Homo sapiens).

Types of hallucinogenic mushrooms

In general, hallucinogenic mushrooms with psychoactive effects are classified into three main groups, including various species within each category.

1. Mushrooms with psilocybin and psilocin

Psilocybin mushrooms contain the hallucinogenic alkaloids psilocybin (4-PO-DMT) and psilocin. When ingested, these compounds produce visual and auditory distortions, altered perception of time and space, and intense emotions. Below, we describe six key genera, with representative species, morphological characteristics, habitats, distribution, potency, and typical effects.

Genus Psilocybe

This genus includes about 350 species distributed worldwide, except in Antarctica. Of these, over 100 are psychoactive. They are saprotrophic mushrooms that typically grow on manure or decaying organic matter. They have a convex to flat cap, dark gills, and a stipe with a ring in many species.

When exposed to air, they may turn bluish due to the oxidation of psilocin, a psychoactive compound that reacts with oxygen. They are commonly found in meadows, forests, and pastures in temperate or tropical climates.

Notable species of the Psilocybe genus:

- Psilocybe cubensis (golden mushroom): The most iconic of the "magic mushrooms." Its cap, with a bright ochre-golden hue and 5 to 8 cm in diameter, along with its stipe with a membranous ring, makes it easily recognizable. It grows on manure in warm and subtropical regions of the Americas, Asia, and tropical Europe. It contains psilocybin (~15 mg/g dry) and psilocin, producing moderate-intensity effects.

- Psilocybe semilanceata ("Liberty cap"): Small but potent, this mushroom has a 2–5 cm bell-shaped cap with a distinctive nipple. Without a ring, it is found in temperate grasslands of Europe and North America, especially in autumn. Its potency is low to medium (up to 0.98% psilocybin dry).

- Psilocybe azurescens ("flying saucers"): One of the most potent in the group. Native to the west coast of the U.S. (Washington and Oregon), it has a convex 7–10 cm cap, reddish-brown, and a light stipe. It contains up to 1.78% psilocybin and 0.38% psilocin, according to chemical analyses.

- Psilocybe mexicana: With a small cap (2–4 cm), this species grows in grasslands and mountains of Mexico and Central America. It has been used for centuries by indigenous peoples like the Mazatec in shamanic rituals.

- Psilocybe cyanescens ("Wavy Caps"): Easily recognizable by its characteristic wavy caps. It grows on decaying wood in temperate climates worldwide.

- Psilocybe argentipes: Endemic to Japan, it thrives in forest soils among oaks, cedars, or loblolly pines.

- Other notable species: P. baeocystis (Oregon), P. pelliculosa (North America and Europe), P. bohemica (Europe), P. samuiensis (Thailand), P. caerulipes (North America).

The effects of psilocybin mushrooms vary depending on the species, dose, individual metabolism, and environment. Generally, they include visual distortions such as geometric shapes or halos, synesthesia (e.g., "seeing" sounds), and a sense of connection with the environment. Physiologically, they may cause a slight increase in blood pressure and heart rate, as well as pupil dilation.

Genus Panaeolus

Panaeolus mushrooms grow on decaying organic matter and stand out for their discreet appearance but potent content. Their cap is small and rounded in early stages, flattening as it matures. They have dark gills and a generally smooth stipe, without a visible ring. Known popularly as "grass shrooms," they are easily found in warm and temperate climates worldwide.

Relevant Panaeolus species:

- Panaeolus cyanescens (also known as Copelandia Hawaiian): Recognizable by its conical to convex cap, dark brown turning almost black with age. It grows on fresh cow or buffalo manure in tropical grasslands of South America, Africa, Asia, and various islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is one of the most potent species: upon contact, it stains a vibrant blue, a sign of its high psilocybin concentration.

- Panaeolus subbalteatus (known as "the banded"): It has a light brown cap adorned with a characteristic gray band. It grows on horse manure and well-fertilized lawns in temperate or subtropical regions.

- Panaeolus antillarum: Similar to the previous, but more adapted to tropical areas. Found in Central America, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa.

- Other psilocybin-containing Panaeolus: P. olivaceus, P. sphinctrinus, P. bisporus, P. tropicalis, P. cambodginensis.

The subjective effects of Panaeolus are comparable to those of the Psilocybe genus. However, some species have a more bitter taste and may cause mild stomach discomfort.

Genus Conocybe

Conocybe mushrooms are delicate, with a conical or bell-shaped cap and a slender stem. They grow in grasslands, meadows, or wet mosses, often on cultivated lawns. Many small species in this genus are harmless or simply unknown, but four stand out for their psychedelic content:

- Conocybe siligineoides: A small golden-capped mushroom, only found in grassy areas in Oaxaca (Mexico). Traditionally used by the Mazatec in shamanic rituals.

- Conocybe kuehneriana (formerly Pholiotina kuehneriana): Dark brown cap, filiform stipe, found on lawns in North America and temperate Europe.

- Conocybe cyanopus: Light cap with a bluish stem, seen in Europe on lawns.

- Conocybe smithii (Galerina cyanopus): Similar to C. cyanopus, reported in Europe and the U.S.

- IMPORTANT WARNING: Conocybe filaris (very common on lawns) is NOT psychedelic but deadly poisonous (contains muscarine) and must not be confused with the above. This confusion has caused documented severe poisonings.

In general, psychedelic Conocybe are small and discreet; they should only be collected with absolute certainty of identification and by mycology experts.

Genus Gymnopilus

This genus of "orange mushrooms" comprises over 200 species. They are robust, with yellow-orange gills and rusty spores. They grow on decaying wood or sometimes in soil rich in woody debris.

Author: Tony Wills

Fourteen Gymnopilus species contain psilocybin according to chemical studies, among which we highlight:

- Gymnopilus junonius (Big laughing Gym): Very striking, with a 5–15 cm yellow-orange cap and reddish-brown spores. It grows on stumps of broadleaf or coniferous trees in temperate seasons in Eurasia and North America.

- Gymnopilus luteus (formerly Gymnopilus luteofolius): Yellow to pale orange cap, grows on dead coniferous wood.

- Gymnopilus aeruginosus: Orange cap, psychoactive content.

- Others: G. luteoviridis, G. validipes, G. braendlei, G. luteofolius, etc.

The effects are similar to other psilocybin mushrooms but may also cause nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort. Accurate identification is crucial, as there are morphologically similar toxic species.

Genus Inocybe

Inocybe is a diverse genus of mycorrhizal mushrooms (associated with tree roots). Many are not psychoactive but poisonous (contain muscarine). However, a couple of species with psilocybin have been identified:

- Inocybe aeruginascens: Small mushroom (3–5 cm cap, yellowish-brown with green-blue spots) growing in soil under trees (elm, birch) in Europe and the U.S. It turns blue when damaged. Contains psilocybin, psilocin, baeocystin, and the compound aeruginascin (trimethylated analog).

- Inocybe corydalina: Rarely documented mushroom in Europe that also contains psilocybin.

SAFETY WARNING: Psilocybin Inocybe are extremely rare and very difficult to distinguish from deadly toxic species. Professional mycologists strongly advise against their collection or consumption due to the high risk of lethal confusion.

Genus Pluteus

The Pluteus genus groups mushrooms with free gills and pink spores. Several grow on dead wood or bark. Some contain psilocybin:

- Pluteus salicinus (willow shield): Grows on willow wood in temperate climate forests. Grayish speckled cap, whitish stem.

- Pluteus americanus: On fallen broadleaf logs (U.S., Russia).

- Pluteus cervinus: Common on leaves, rarely reported as psychedelic.

Overall, psilocybin Pluteus are less potent compared to classic Psilocybe; their effects are usually short-lived and moderate.

2. Mushrooms with muscimol (ibotenic acid)

This group includes mushrooms that do not contain psilocybin but other psychoactive compounds like ibotenic acid and muscimol. Both act on the GABA system, a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, producing effects very different from those caused by psilocybin.

These compounds induce altered states of consciousness often described as dreamlike, dissociative, or even sedative, depending on the dose and environment. The most well-known mushrooms containing these substances primarily belong to the Amanita genus, with the most iconic being:

Amanita muscaria: the red mushroom of fairy tales

With its red cap speckled with white warts, Amanita muscaria is one of the most recognizable mushrooms in the world. As it matures, its cap flattens and varies from red to orange, with white warts, gills, and a white stem, ring, and volva at the base. It grows in symbiosis with pines, birches, and other species in temperate climates of the northern hemisphere, though it has also been introduced to other continents.

It contains ibotenic acid and muscimol, psychoactive compounds with effects very different from psilocybin mushrooms. After consumption (usually dried or cooked), it produces a phase of excitation followed by sedation, dizziness, confusion, nausea, and dreamlike hallucinations. High doses can cause stupor or coma, though deaths are rare.

CAUTION: Despite its historical use, toxicology experts strongly advise against consuming any Amanita due to the risk of severe adverse reactions, including liver failure.

Amanita pantherina (panther cap)

Known as "Panther cap," Amanita pantherina is a mushroom with a brown to cream cap (4–10 cm), decorated with white warts that may disappear with rain. Though less striking than A. muscaria, it is more potent and is found in broadleaf and mixed forests of Europe, Asia, and North America.

It contains high concentrations of muscimol and ibotenic acid, causing more narcotic effects: intense drowsiness, ataxia, and vivid hallucinations. Its toxicity is high and can induce stupor or coma at high doses. Its traditional use is rare, and like other ibotenic Amanitas, it is considered highly dangerous.

Several similar Amanitas contain these alkaloids:

- Amanita gemmata: Golden-yellow cap, white gills, smaller size. Grows in temperate forests.

- Amanita regalis (or clasping amanita): Similar to muscaria but dark brown. Found in northern forests.

3. Parasitic mushrooms

This section includes entomopathogenic fungi (which infect insects) or plant parasites, capable of producing substances with effects on the nervous system. Though less known than psilocybin-containing species, these fungi represent a fascinating field of study due to the diversity of bioactive compounds they synthesize.

Claviceps purpurea: the ergot fungus and the origin of LSD

Claviceps purpurea, known as ergot of rye, is not a mushroom in the classic sense but an ascomycete parasitic fungus that infects cereal spikes like rye. In contaminated grains, it forms dark sclerotia known as ergot, rich in ergot alkaloids such as ergotamine, ergometrine, and ergocryptine.

These compounds, though not classic hallucinogens, have potent effects on the nervous and circulatory systems. Their consumption caused ergotism for centuries, a poisoning that could lead to gangrene due to severe vasoconstriction, seizures, and delirious states with visions.

Chemist Albert Hofmann managed to isolate LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) from ergot, marking the start of the modern era of psychedelics. Claviceps purpurea is thus the ancestral source of LSD and a key figure in the history of entheogens.

Hallucinogenic mushrooms connect us to a rich ancestral tradition but also to an emerging scientific frontier. Understanding their diversity, active compounds, and effects is the first step toward a more conscious, ethical, and responsible use.

Complete references

- Hofmann, A., Heim, R., Brack, A., & Kobel, H. (1958). Psilocybin, ein psychotroper Wirkstoff aus dem mexikanischen Rauschpilz Psilocybe mexicana Heim. Experientia, 14(3), 107-109.

- Schultes, R. E., & Hofmann, A. (1979). Plants of the gods: Origins of hallucinogenic use. McGraw-Hill.

- Wasson, R. G. (1957). Seeking the magic mushroom. Life Magazine, 42(19), 100-120.

- Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264-355.

- Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., & Emrich, H. M. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addiction Biology, 7(4), 357-364.

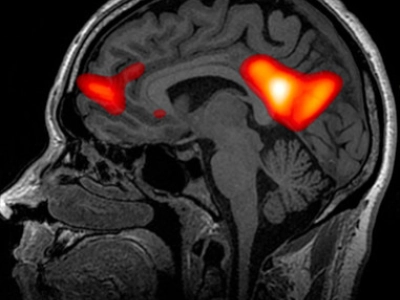

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., et al. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(6), 2138-2143.

- Barrett, F. S., Griffiths, R. R. (2018). Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: Phenomenology and neural correlates. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 36, 393-430.

- Griffiths, R. R., et al. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268-283.

- Carbonaro, T. M., et al. (2016). Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: Acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1268-1278.

- Barrett, F. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2015). Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 29(11), 1182-1190.

- Studerus, E., Kometer, M., Hasler, F., & Vollenweider, F. X. (2011). Acute, subacute and long-term subjective effects of psilocybin in healthy humans: a pooled analysis of experimental studies. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(11), 1434-1452.