Psilocybin: what it is, how it works and what effects it has

- What is psilocybin?

- Brief history and rediscovery

- How psilocybin acts in the organism

- Duration and pharmacokinetics of psilocybin

- Effects of psilocybin consumption

- Psychological and perceptual effects

- Physiological effects

- Factors influencing the experience

- Psilocybin risks and precautions

- Psychological risks

- Physical risks

- "Bad trips" and their causes

- Interactions with other substances

- Demystifying myths

Psilocybin is a psychoactive compound present in more than 200 species of mushrooms, popularly known as "magic mushrooms." Its history transits between the ritual and the clinical, the spiritual and the forbidden, in a constant tension that reflects its cultural and pharmacological complexity.

For centuries, it has been used for ceremonial and healing purposes by various indigenous cultures, especially in Mesoamerica. In recent decades, it has reemerged in the scientific and medical fields as a promising tool to explore consciousness and treat resistant mental disorders. But what exactly is this substance? How does it interact with the human body? Why does it provoke such intense and, in some cases, transformative experiences?

This article proposes a journey through the origin, nature, and effects of psilocybin: from forest mushrooms to contemporary laboratories. In a second installment, we will explore its therapeutic applications and its changing legal situation worldwide.

What is psilocybin?

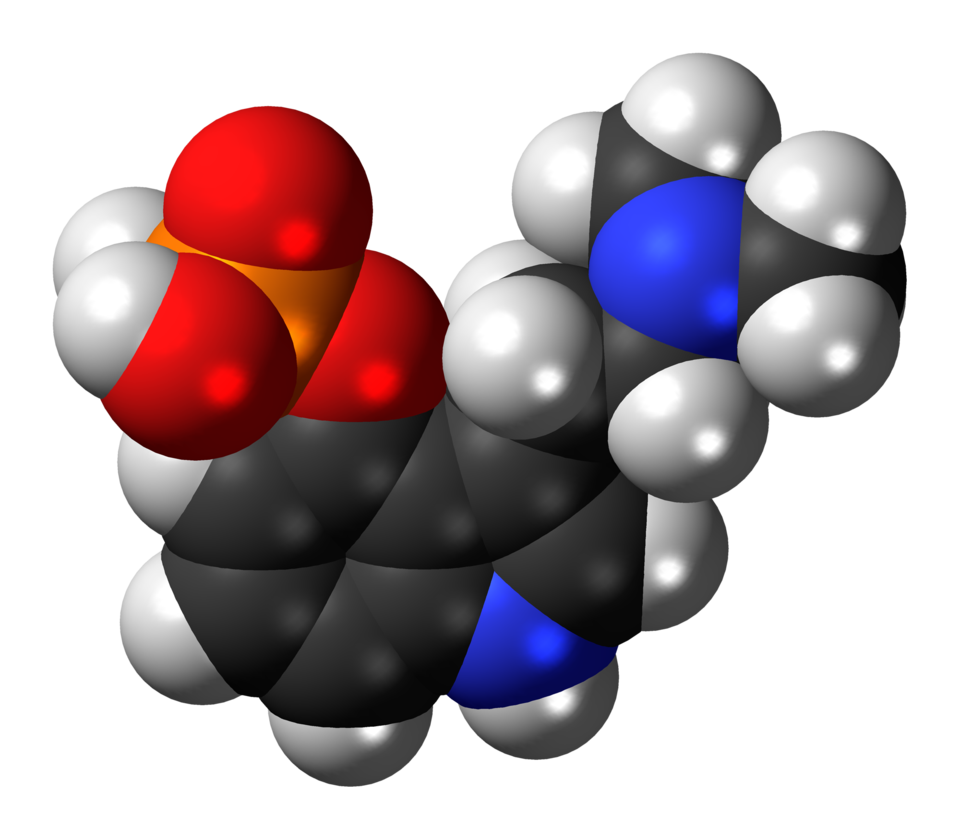

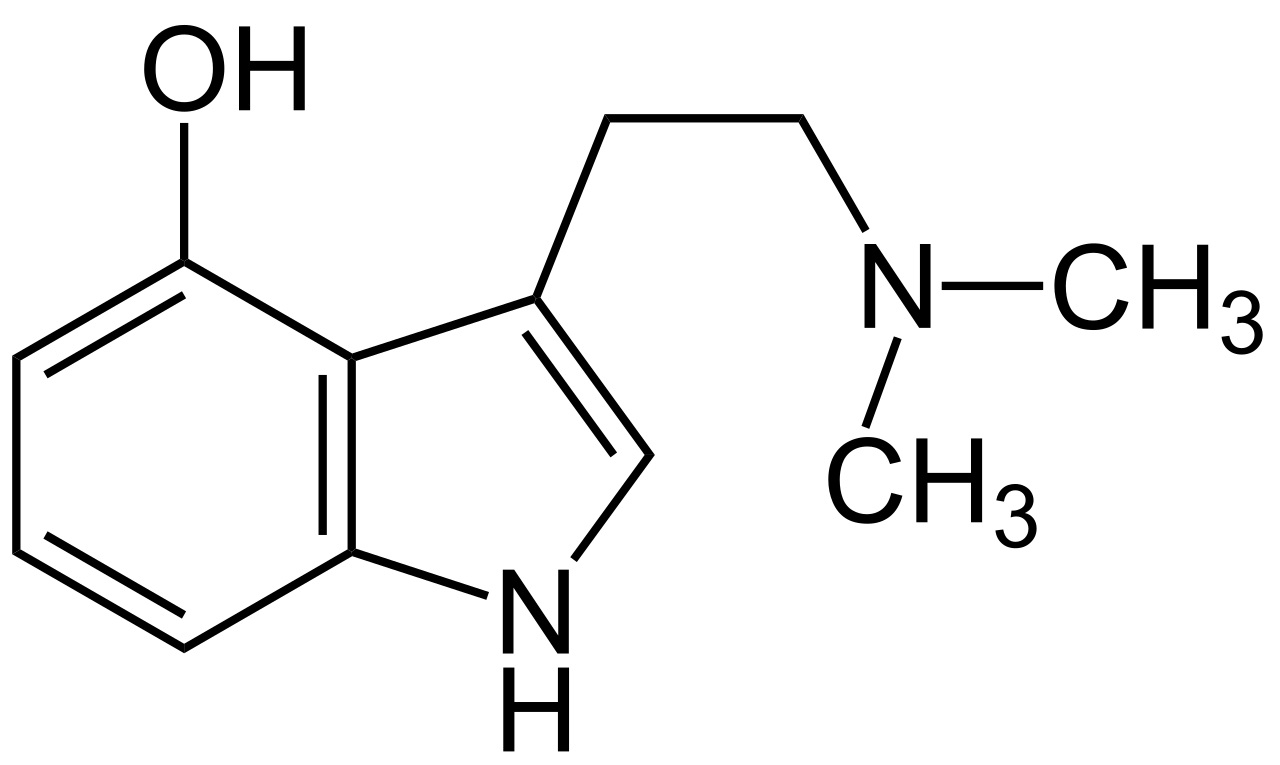

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring tryptamine alkaloid, whose structure bears similarities to serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood, sleep, and sensory perception. Its chemical formula is C₁₂H₁₇N₂O₄P, and its structure is based on an indole ring with an added phosphate group. However, psilocybin does not act directly on the brain. It is a prodrug, meaning a substance that requires transformation in the organism to exert its effect. This conversion occurs in the liver, where specific enzymes remove the phosphate group, converting it into psilocin (C₁₂H₁₆N₂O), the truly active compound at the neurological level.

Psilocin has high affinity for various serotonergic receptors, especially the 5-HT2A subtype, involved in the modulation of consciousness, sensory perception, and sense of self. Psilocybin is found in a wide variety of mushrooms, mainly from the Psilocybe genus, but also in species of Panaeolus, Gymnopilus, or Copelandia. The concentration of the compound varies according to species, genetics, environment, and mushroom maturity.

Since its laboratory isolation in 1958 by Albert Hofmann, it can also be obtained synthetically, with this version being chemically identical to the natural one and the most used in clinical studies for its purity and controlled dosage.

Brief history and rediscovery

Gordon Wasson and psychedelic mushrooms

The Wall Street banker who revealed the sacred mushrooms of Mexico and forever changed our understanding of psychedelia. The fascinating story of R. Gordon Wasson.

Read moreThe ritual use of psilocybin mushrooms is documented in numerous Mesoamerican indigenous cultures. The Mexica, for example, knew them as teōnanácatl — "flesh of the gods" — and used them in religious ceremonies. These practices were suppressed during colonization but survived in communities like the Mazatec of Oaxaca, where traditional forms of use are still preserved today.

Western interest resurfaced in 1955, when banker and amateur ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson participated in a ceremony with María Sabina, a Mazatec healer. His experience, published in Life magazine, marked the beginning of a new stage of psychedelic exploration in the West. In 1958, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, known for his discovery of LSD, succeeded in isolating and synthesizing psilocybin, which facilitated its study in scientific contexts.

During the 1960s, the substance was the subject of interest in both clinical and countercultural spheres, until it was banned in the 1970s. Only in the 21st century, after decades of silence, has it returned to a place in scientific research, with rigorous studies exploring its efficacy in mental health treatments.

What began as an ancestral practice marginalized by colonization, today returns to the spotlight as one of the most promising frontiers of neuroscience and mental health.

How psilocybin acts in the organism

Once ingested, psilocybin is rapidly converted to psilocin by the enzyme alkaline phosphatase. Psilocin, being similar to serotonin, binds to its receptors, especially 5-HT2A, causing a temporary alteration in neuronal communication.

Neuroimaging studies have shown that psilocin reduces the activity of the default mode network, a brain structure associated with self-reference, rumination, and ego construction. At the same time, it increases global connectivity between brain regions that normally do not interact with each other, giving rise to a more flexible and less hierarchical network. Additionally, an increase in neural entropy has been observed, that is, in the complexity and unpredictability of brain activity patterns, a phenomenon linked to ego dissolution and the emergence of mystical or non-ordinary states of consciousness.

Duration and pharmacokinetics of psilocybin

- Onset of effects: 20–60 minutes after ingestion.

- Peak intensity: between 1.5 and 3 hours.

- Total duration: 4 to 6 hours, depending on dose, metabolism, and environment.

Most psilocin is eliminated within hours through urine. It leaves no cumulative toxic residues and generates no known physical dependence.

Effects of psilocybin consumption

The experience with psilocybin is profoundly subjective and depends on multiple individual and contextual factors. Although there are no universal effects, common patterns have been identified in the psychological, sensory, and physiological responses it provokes.

Some describe the experience as profoundly revealing, mystical, or therapeutic; others, as confusing, overwhelming, or even terrifying if it doesn't occur under adequate conditions.

Psychological and perceptual effects

From a psychological perspective, psilocin — the active form of psilocybin — profoundly alters the processing of sensory and cognitive information, which can lead to experiences that challenge ordinary logic or the boundaries of the self.

Some of the most common effects include:

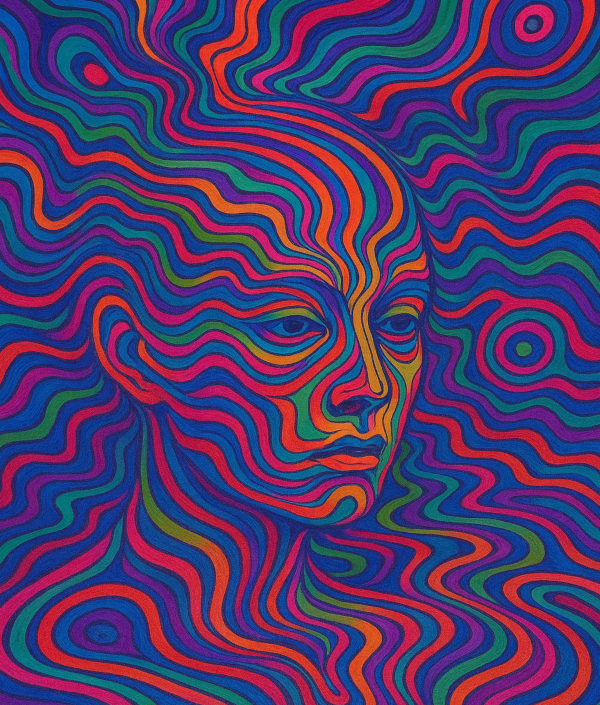

- Sensory alterations: intensified colors, sharper textures, more enveloping sounds. The appearance of geometric patterns when closing the eyes (closed-eye visuals) and even visual hallucinations or synesthesia (perceiving sounds as colors, for example) are frequent.

- Distortion of time and space: many users report a sensation of time stopping or dissolving, as well as changes in the perception of distances or one's own body.

- Changes in self-perception: a sensation of deep introspection may arise, of "seeing from outside" one's own mind, or even ego dissolution, where the boundary between self and environment disappears.

- Emotional elevation and mystical states: feelings of awe, unity, compassion, or spiritual "revelation" are common, especially with high doses or in introspective contexts.

- Psychological challenges: moments of intense anxiety, confusion, obsessive thoughts, or paranoia may also appear, especially if the environment is not adequate or if the person has a psychological predisposition.

"I felt I was not a person, but a process. That I was merged with everything. It was beautiful, but also unsettling." — Anonymous participant in a clinical study (Johns Hopkins, 2016)

Physiological effects

At the physical level, psilocybin produces relatively mild effects compared to its psychological intensity. It generates no relevant systemic toxicity nor known physical dependence.

The most frequent bodily effects include:

- Mydriasis (pupil dilation). Slight increase in heart rate and sometimes blood pressure.

- Nausea or gastrointestinal discomfort, especially when consuming raw or dried mushroom fruiting bodies.

- Mild tremors, chills, or sweating.

- Decreased appetite.

- Alteration of balance or motor coordination.

These effects are usually transitory and disappear along with the substance's metabolism.

Factors influencing the experience

Variability in the psilocybin experience is determined by multiple factors. In the scientific and therapeutic field, the concept of "set & setting" is used, which refers to:

- Set (mental state): emotions, expectations, psychological health.

- Setting (environment): place, company, sensory stimuli.

- Dose and species: potency varies between species and between fruiting bodies.

- Cultural context: beliefs and interpretive frameworks can modulate the experience.

- Personal vulnerability: psychiatric history or complex emotional situations.

Psilocybin risks and precautions

Although psilocybin is considered a substance of low physiological toxicity and does not generate physical dependence, it is not without risks, especially when consumed in uncontrolled contexts, without adequate knowledge, or in people with psychological vulnerabilities. Understanding these risks does not seek to demonize its use, but to promote a more informed, respectful, and safe approach.

Psychological risks

The most relevant risk associated with psilocybin consumption is psychological, not physical. The intensity of its effects can lead to emotionally overwhelming experiences, especially in inadequate contexts.

Some of the most reported adverse effects include:

- Acute anxiety or panic attacks during the trip.

- Depersonalization or sensation of losing control of one's own mind or identity.

- Paranoia or persecutory thoughts.

- In exceptional cases: temporary psychotic episodes, especially in people with a history of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other latent psychotic disorders.

Most of these effects are transitory but can be very distressing at the moment. Therefore, consumption without adequate emotional preparation is discouraged, especially in people with a history of mental disorders or unresolved trauma.

Physical risks

From a physiological standpoint, risks are lower but not non-existent. Misidentification of wild mushroom species constitutes a real and potentially fatal risk. Some toxic species, like Amanita phalloides, can be confused with psilocybin mushrooms by inexperienced people.

Consumption of large quantities can produce nausea, vomiting, tremors, and confusion.

While there is no evidence of acute hepatic or renal toxicity in humans, the experience can generate accidents or reckless behaviors, especially in unsupervised environments.

"Bad trips" and their causes

The so-called bad trip is not an intoxication in the clinical sense, but a psychologically negative experience characterized by:

- Confusion, existential anguish, sensation of being trapped.

- Dark thoughts or confrontation with repressed traumas.

- Fear of having permanently "damaged" the mind (something not supported by scientific evidence if there are no serious psychiatric antecedents).

These effects are usually related to an inadequate environment, high doses, or the absence of guidance or accompaniment. In well-structured clinical or ritual contexts, the incidence of these episodes decreases significantly.

If you want to delve deeper into essential precautions before a psilocybin experience, you can consult the following articles that gather key recommendations for informed, safe, and responsible use.

Bad trips with psilocybin: how to avoid a bad trip

Find out what a bad magic mushroom trip is, how to prevent it and what to do if it happens. At Mushverse, we guide you to a safe and transformative experience.

Read moreInteractions with other substances

Psilocybin can interact unpredictably with other substances, both pharmacological and recreational. Some combinations can increase adverse effects, decrease its therapeutic efficacy, or even generate serious risks to mental or physical health.

Here are some important interactions to know and avoid:

- Antidepressants and serotonergic drugs (SSRIs, MAOIs, SNRIs): may reduce psilocybin's effects or generate a serotonin overload, increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome, a potentially dangerous condition.

- Stimulants (amphetamines, MDMA, cocaine): combining them with psilocybin can overload the nervous system, increase blood pressure, and provoke states of anxiety or paranoia.

- Alcohol: can attenuate the clarity of the experience, increase disinhibition, and favor unpredictable reactions or risky behaviors.

- THC (cannabis): the interaction is highly variable. In some people, it may potentiate visual or introspective effects, but in others increase anxiety, confusion, or "bad trips."

- Anxiolytics and antipsychotics: usually block or soften psychedelic effects, which is why they are sometimes used in clinical contexts to "land" an intense experience. Their combination outside a controlled environment can be counterproductive.

- Other psychedelic substances (LSD, DMT, mescaline...): mixing different psychedelics can be unpredictable and overload the experience, increasing the risk of dissociation, panic, or prolonged confusion.

Demystifying myths

Despite its growing acceptance in medical research, psilocybin remains surrounded by myths inherited from late 20th-century misinformation.

Among the most common myths:

- "It stays in the spinal cord": false. Psilocin is metabolized and eliminated within hours, with no tissue accumulation.

- "One time and you go crazy": there is no evidence of permanent brain damage in people without psychiatric predisposition.

- "It's a soft and harmless drug": although not toxic in the classic sense, its psychological potency demands respect and preparation.

In upcoming articles, we will address its clinical applications and the current debate around its regulation. We invite you to continue exploring this fascinating psychedelic universe.

Until the next journey!

This article is for informational and educational purposes only. Psilocybin is regulated or prohibited in many countries. Its consumption is not promoted and it is not considered suitable for human use outside authorized clinical contexts.

References

- https://maps.org/

- https://www.beckleyfoundation.org/science/substances-methods/psilocybin/

- https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1654/psilocybin

- https://pharmrev.aspetjournals.org/article/S0031-6997(24)01182-7

- https://archive.org/details/dispositionoftox0000base_v7n5

- https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%ADndrome_serotonin%C3%A9rgico

- https://hopkinspsychedelic.org/